Though the numbers aren’t fully known for all cancer groups, there appears to be an increased risk of developing frozen shoulder after some cancer surgeries. Specifically, in the breast cancer population, approximately 10.3% of people will develop frozen shoulder after breast cancer surgery [1]. This occurrence is over 3 times higher than the general population (where approximately 1-3% of individuals will develop a frozen shoulder in their lifetime) [2, 3].

I also frequently get questions about frozen shoulder, so this blog will outline some of the key information that is helpful to understand.

What is a Frozen Shoulder?

The term “frozen shoulder” is often overused to describe anyone who has a painful and stiff shoulder. However, a true frozen shoulder has a very specific presentation in terms of how it progresses and the pattern in which movement is lost.

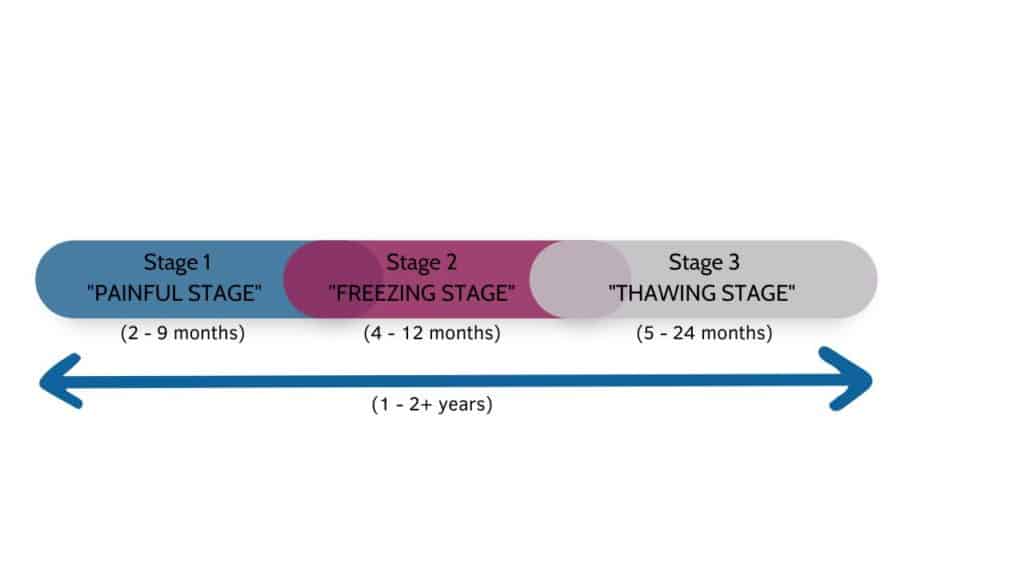

There are 3 overlapping phases of frozen shoulder [3] and the entire process can take 1-2 years to complete. Some research has even shown that many people still experience some symptoms up to 6 years later [3]! Unfortunately, as much as people want to speed this process along, a true frozen shoulder has a slow timeline for healing.

(1) Stage 1: The Painful Stage (lasting 2-9 months*)

At this stage, pain in the affected shoulder gradually increases over a period of weeks to months. The pain may be in the shoulder itself, but often refers down the upper arm. The neck and upper back may also gradually become painful as your body tries to guard, protect and compensate for the pain. The pain often is worse at night, which significantly disrupts sleep.

Though everyone’s pain levels will be different, reaching out to the side and behind the back can be particularly painful. Sudden motions of that arm are also aggravating. You may also begin to notice these movements becoming stiffer (see stage 2).

(2) Stage 2: The Freezing Stage (lasting 4 – 12 months*)

This stage typically overlaps with stage 1, as most people begin to lose shoulder motion as the pain continues to increase. As this stage begins, you will begin to notice a gradual and progressive loss of shoulder movement in a very specific pattern (this is really what differentiates a frozen shoulder from other problems). In the order of motion loss, you will notice the following movements becoming stiff:

– External rotation (turning your hand away from your body)

– Abduction (reaching your arm out to the side)

– Internal rotation (reaching your hand behind your back)

– Extension (extending your arm straight backwards)

The good news about this phase is that, at some point, the pain typically begins to decrease. The shoulder stiffness is what really becomes obvious when this stage is in “full swing.”

(3) Stage 3: The Thawing Stage (Lasting 5-24 months*)

This is the time when people begin to notice small (but important) movements becoming a little easier: being able to reach their head to wash their hair, being able to get the cup of the kitchen shelf, being able to put that shirt on more easily.

Over time, and with practice, these motions will become better and better.

(*Timelines based on Challoumas et al article)

Causes of Frozen Shoulder

Unfortunately, we still don’t know exactly why frozen shoulder occurs. Research [2] has shown that women are more commonly impacted, and these women are often in the age range of 40 – 70 years old (i.e. peri/post-menopausal). This brings into question the possible role of hormonal changes (hello women going through breast and ovarian cancer treatment), but more research is needed.

A study investigating the relationship between frozen shoulder and breast cancer treatment showed that women who had a mastectomy and/or breast reconstruction were at a greater risk of developing a frozen shoulder (vs those who did not). (Yang et al)

So based on the above studies, there are several factors that might put you at a higher risk of developing frozen shoulder after cancer surgery:

– Female*

– Aged 40-70

– Underwent a mastectomy

– Underwent breast reconstruction

(*Note: For the purposes of this blog, I use the term “female” to indicate any person whose sex assignment at birth was female.)

Treatment for Frozen Shoulder

Despite the existence of many studies on the treatment of frozen shoulder, there is no consensus on a single best way to treat it [2]. (I think that this is, in part, because we don’t fully understand WHY it happens in the first place.)

A 2020 systematic review by Challoumas et al [3] showed that, for individuals with frozen shoulder of less than 1 year duration, a corticosteroid injection into the shoulder joint (called an intra-articular injection) provided the best outcomes in terms of short-term pain relief and function. This study also showed that the benefits were even greater when a corticosteroid injection was combined with exercise and physiotherapy.

How Cancer Rehab Can Help

By understanding what the evidence shows for the treatment of frozen shoulder in the general population, we can extrapolate to apply it to individuals recovering from and/or going through cancer treatment. A conservative approach using exercise and physiotherapy can be helpful in reducing pain, improving shoulder movement and improving overall function. An intra-articular corticosteroid injection may provide additional relief, but the risks and benefits must be discussed with a knowledgeable orthopedic or sports medicine specialist.

Indeed, it is my clinical experience that physiotherapy, when properly applied depending on the stage of frozen shoulder, can be very helpful. We cannot stop a frozen shoulder once it has begun nor can we “speed up” the natural process, but physiotherapy can help manage pain, improve mobility and function.

In addition, our shoulder does not move in isolation. A LOT of compensation and protection strategies develop during the earlier stages of frozen shoulder. Other body parts like the ribs, the neck, the thoracic spine, the shoulder blade, the collarbone, the surrounding fascia and muscles ALL become stiff and restricted by not being used “optimally” over such a long period of time. As a result, physiotherapy at any stage of frozen shoulder should also be directed to these other body parts to ensure they continue to move as best as possible. This will make later treatment MUCH more effective (not to mention faster and less frustrating!)

When to Contact your Medical Team?

To summarize, based on the research and my clinical experience, here is how Cancer Rehab Physiotherapy Can Help if you develop a frozen shoulder during or after your cancer treatment

Stage 1

- Pain management strategies

- Maintaining shoulder mobility (within reason)

- Keeping other joints, muscle and fascia moving

- * Talk with your doctor about the risks/benefits of an intra- articular corticosteroid injection for further pain relief

Stage 2

Keeping other joints, muscle and fascia moving

Modifying regular activities based on your shoulder mobility

* Talk with your doctor about the risks/benefits of an intra- articular corticosteroid injection for further pain relief (If your

frozen shoulder began less than 1 year ago)

Stage 3

Restoring shoulder mobility

Restoring active control of your shoulder girdle

Returning to regular activities and sports

Disclaimer – These blogs are for general information purposes only. Medical information changes daily, so information contained within these blogs may become outdated over time. In addition, please be aware that the information contained in these blogs is not intended as a substitute for medical advice or treatment and you should always consult a licensed health care professional for advice specific to your treatment or condition. Any reliance you place on this information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

References

- Yang, S., Park, D. H., Ahn, S. H., Kim, J., Lee, J. W., Han, J. Y., Kim, D. K., Jeon, J. Y., Choi, K. H.,

& Kim, W. (2017). Prevalence and risk factors of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder after breast

cancer treatment. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of

Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(4), 1317–1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3532-4 - Nakandala, P., Nanayakkara, I., Wadugodapitiya, S., & Gawarammana, I. (2021). The efficacy

of physiotherapy interventions in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis: A systematic

review. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation, 34(2), 195–205.

https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-200186 - Challoumas, D., Biddle, M., McLean, M., & Millar, N. L. (2020). Comparison of Treatments for

Frozen Shoulder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA network open, 3(12),

e2029581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29581